Child labour

International Child Labour Day turns harsh spotlight on India, with the highest number of working children in the world.

Bangalore, India - Across the globe more than 150 million children

between age five and 14 are involved in child labour, while India is

home to the highest number of working children in the world.

On International Day Against Child Labour on Friday, attempts are under way to put a stop to it. In India, more than 28 million children have jobs, according to UNICEF estimates.

India's current child labour law prohibits children under the age of 14 from being employed in hazardous jobs.

However, in May this year, rather than encouraging a complete abolition of child labour in the country, the cabinet headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved only amendments to the law.

"We live in a country where it is very normal for a farmer's son to help the farmer after school hours or for an artisan's children to learn the craft. So we don't want this form of work to be penalised as child labour," a labour ministry official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Al Jazeera.

"That's why we've clearly stated that this form of work won't be punished," he said. "If a person breaks the law, the justice system is there."

Although cabinet approval does not necessarily mean the bill

will pass into law, it has prompted strong reactions in the country.

The Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), an NGO headed by 2014 Nobel Peace laureate Kailash Satyarthi, welcomed approval of the amendment bill.

"Currently, as the law stands, children under the age of 14 are not allowed to work in only 18 occupations and 65 processes that are deemed to be hazardous," explained Bhuwan Ribhu, an activist and lawyer with the BBA.

Feature: Child labourers share their stories on World Day against Child Labour

"This amendment bill allows for all forms of child labour to be prohibited until the age of 14 years," he said.

The law is "a welcome step", said Ribhu. "It's also welcome because rehabilitation is an integral part of the law. Employment of children has been made a cognisable offence and repeat offence is also a non-bailable offence," said the lawyer.

Ribhu added a word of caution, however.

"It is very important for the law to be worded in such a way that it is not open to misuse. There is a difference between children working in families and child labour in family enterprises. And that has not yet been made clear.

"Child labour needs to be defined clearly in the law so that children are not exploited in the name of family-based work," Ribhu said.

A recent UN report said

nearly 300 million people still live under poverty in India. For a

country with extreme inequalities, an abolitionist approach may not be a

practical solution.

However, Ribhu pointed out that "poverty is also perpetuated with the exploitation of children".

"Currently there are about as many unemployed adults in India as there are working children. So these jobs are being taken by children instead of adults in the name of cheap labour," he said.

"Trafficking of children for forced labour has become one of the largest organised crimes in the world and I am afraid that it will continue in the name of family enterprises."

In the 35 years since its establishment, the BBA has rescued more than 83,500 working children from across 18 states in India.

Just this week, the organisation rescued 26 children from New Delhi and four from Bangalore.

Other organisations working in the field take a different approach to child labour.

Nandana Reddy, co-founder of Concerned for Working Children (CWC), challenged the narrative of "saving childhood" that dominates discussions on the issue.

"There are moralists who believe that children have to enjoy this beautiful childhood, this utopian childhood, which doesn't really exist," Reddy said.

"We have millions of working children in India. Now you can't rescue all of them and put them in remand homes," she added. "That's absolutely ridiculous. By putting them into remand homes, you are violating a whole set of rights. This approach has not changed in decades."

Reddy said she found the amendment to the bill alarming.

"Allowing children to work in family or family-based occupations can be a throwback to the Sivakasi days, where the match and firework industry was all run by family-based enterprises. It's a way for the industry to use cheap labour and, what we call, invisible hands," Reddy said.

Instead, the government should provide jobs for children in the formal sector that can be monitored, she said.

The Bangalore-based CWC played an instrumental role in setting up Asia's first working children's union called the Bhima Sangha back in 1990. Twenty-five years later, the Bhima Sangha continues to help working children unionise and fight for their rights.

Sivraju, 13, is a member of Bhima Sangha. He works and attends school in Bangalore.

Sivraju's parents moved here from the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh in search of better job opportunities to help build a new house back in their village.

When Sivraju is not at school, he cleans water tanks and roads in his neighbourhood.

"I work because I can make money. I get paid about 200 rupees for an hour's work ($3). I give most of the money to my parents. I keep about 30-40 rupees ($0.50) with me and I use it to buy food for my little sister," he said.

"I like to work because it pays me money and I can give it to my parents," Sivraju added.

Sivraju, who recently passed the seventh grade exams, wants to

be a doctor when he grows up. For Sivraju, Bhima Sangha is an important

place to meet other children.

"At the Bhima Sangha, we get to learn about our rights and we also find out about education and other things related to school," he explained.

But, the possibility of a law prohibiting children from working is problematic for Sivraju.

"I need money to buy books and pens and pencils, and to pay my fees," he said. "How can I stop working?"

On International Day Against Child Labour on Friday, attempts are under way to put a stop to it. In India, more than 28 million children have jobs, according to UNICEF estimates.

India's current child labour law prohibits children under the age of 14 from being employed in hazardous jobs.

However, in May this year, rather than encouraging a complete abolition of child labour in the country, the cabinet headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved only amendments to the law.

"We live in a country where it is very normal for a farmer's son to help the farmer after school hours or for an artisan's children to learn the craft. So we don't want this form of work to be penalised as child labour," a labour ministry official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Al Jazeera.

"That's why we've clearly stated that this form of work won't be punished," he said. "If a person breaks the law, the justice system is there."

|

| A boy works on a construction sites in Electronic City in Bangalore [Felix Gaedtke/Al Jazeera] |

The Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), an NGO headed by 2014 Nobel Peace laureate Kailash Satyarthi, welcomed approval of the amendment bill.

"Currently, as the law stands, children under the age of 14 are not allowed to work in only 18 occupations and 65 processes that are deemed to be hazardous," explained Bhuwan Ribhu, an activist and lawyer with the BBA.

Feature: Child labourers share their stories on World Day against Child Labour

"This amendment bill allows for all forms of child labour to be prohibited until the age of 14 years," he said.

The law is "a welcome step", said Ribhu. "It's also welcome because rehabilitation is an integral part of the law. Employment of children has been made a cognisable offence and repeat offence is also a non-bailable offence," said the lawyer.

Ribhu added a word of caution, however.

"It is very important for the law to be worded in such a way that it is not open to misuse. There is a difference between children working in families and child labour in family enterprises. And that has not yet been made clear.

"Child labour needs to be defined clearly in the law so that children are not exploited in the name of family-based work," Ribhu said.

|

| India's child labour law prohibits children under the age of 14 from being employed in hazardous jobs [Felix Gaedtke/Al Jazeera] |

However, Ribhu pointed out that "poverty is also perpetuated with the exploitation of children".

"Currently there are about as many unemployed adults in India as there are working children. So these jobs are being taken by children instead of adults in the name of cheap labour," he said.

"Trafficking of children for forced labour has become one of the largest organised crimes in the world and I am afraid that it will continue in the name of family enterprises."

In the 35 years since its establishment, the BBA has rescued more than 83,500 working children from across 18 states in India.

Just this week, the organisation rescued 26 children from New Delhi and four from Bangalore.

|

| NGOs such as the Concerned for Working Children in Bangalore are trying to help children escape work [Felix Gaedtke/Al Jazeera] |

Nandana Reddy, co-founder of Concerned for Working Children (CWC), challenged the narrative of "saving childhood" that dominates discussions on the issue.

"There are moralists who believe that children have to enjoy this beautiful childhood, this utopian childhood, which doesn't really exist," Reddy said.

"We have millions of working children in India. Now you can't rescue all of them and put them in remand homes," she added. "That's absolutely ridiculous. By putting them into remand homes, you are violating a whole set of rights. This approach has not changed in decades."

Reddy said she found the amendment to the bill alarming.

"Allowing children to work in family or family-based occupations can be a throwback to the Sivakasi days, where the match and firework industry was all run by family-based enterprises. It's a way for the industry to use cheap labour and, what we call, invisible hands," Reddy said.

Instead, the government should provide jobs for children in the formal sector that can be monitored, she said.

|

| Many working children in India's big cities come from migrant families, who leave their villages in search of better opportunities [Felix Gaedtke/Al Jazeera] |

Sivraju, 13, is a member of Bhima Sangha. He works and attends school in Bangalore.

Sivraju's parents moved here from the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh in search of better job opportunities to help build a new house back in their village.

When Sivraju is not at school, he cleans water tanks and roads in his neighbourhood.

"I work because I can make money. I get paid about 200 rupees for an hour's work ($3). I give most of the money to my parents. I keep about 30-40 rupees ($0.50) with me and I use it to buy food for my little sister," he said.

"I like to work because it pays me money and I can give it to my parents," Sivraju added.

|

| CWC is known for the creation of the Bhima Sangha, Asia's first union for working children [Felix Gaedtke/Al Jazeera] |

"At the Bhima Sangha, we get to learn about our rights and we also find out about education and other things related to school," he explained.

But, the possibility of a law prohibiting children from working is problematic for Sivraju.

"I need money to buy books and pens and pencils, and to pay my fees," he said. "How can I stop working?"

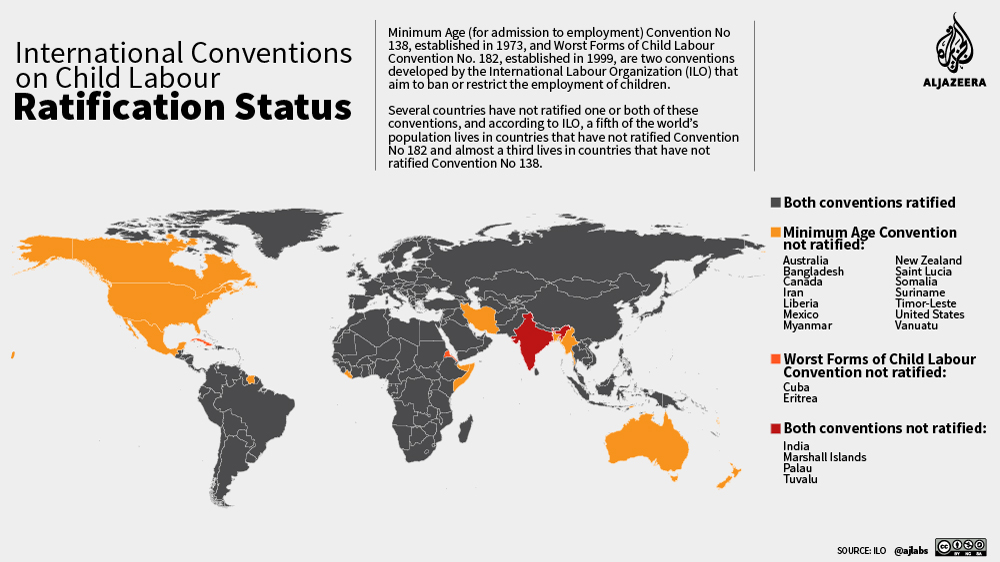

|

| Infographic: Child labour: Where do countries stand? [Al Jazeera] |

Source: Al Jazeera

No comments:

Post a Comment