WORLD'SUNTOLDSTORIES

October 28, 2011 -- Updated 1344 GMT (2144 HKT)

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- In South Africa the full scope of 'corrective rape' is not known because cases are not separated from other forms of rape

- 'Corrective rape' is where men rape lesbians in the belief it can can make them straight

- Zukiswa Gaca tells how she was raped and had to push police to investigate properly

- In South Africa, gay rights are constitutionally protected and activists want 'corrective rape' to legally be a hate crime

Lesbians in South Africa say they are

threatened and victimized by men who believe they can "cure" them by

raping them. Watch CNN International's "World's Untold Stories" Saturday and Sunday.

Cape Town, South Africa (CNN) -- It was supposed to

be an ordinary night out with friends for 20-year-old Zukiswa Gaca but

it ended with her lying on a railway track attempting to take her own

life.Gaca was at a bar, drinking with friends in Khayelitsha township, less than 40 kilometers outside Cape Town, South Africa, when a man tried to ask her out.

"I told the guy that no I'm a lesbian so I don't date guys and then he said to me, 'no I understand. I've got friends that are lesbians, that's cool, I don't have a problem with that.'"

Gaca says he was nice and she trusted him, and they left the bar to go to the home of one of his friends, and that is where his friendly exterior turned nasty.

"He said to me, 'you know what? I hate lesbians and I'm about to show you that you are not a man, as you are treating yourself like a man,'" she told CNN.

'I was raped for being a lesbian'

'Corrective rape' unrecognized in S.A.

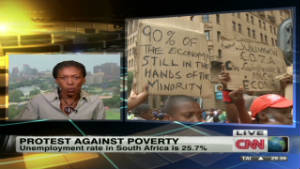

S. African youth ask for economic freedom

South Africa's protest against poverty

"I tried to explain 'I'm not a man. I never said I'm a man, I'm just a

lesbian'. And he said, 'I will show you that I am a man and I have more

power than you.'"Then he raped her, she says, as his friend watched.

Gaca said: "[Afterwards] I went to the railway train road, because I was suicidal at the time. I was lying on the tracks. I think the train was 100 meters away from where I was. Then some other guy came and grabbed me. The train passed. He called the police."

It is called "corrective rape" - where men force themselves on lesbians, believing it will change their sexual orientation.

The extent of the problem is hard to know as South African police do not compile corrective rape statistics separately from other rape cases.

But human rights groups in the country -- where gay rights are constitutionally protected -- are outraged.

Cherith Sanger, of the Women's Legal Centre in Cape Town, which provides legal support for rape victims who cannot afford good lawyers, said: "We believe that corrective rape warrants greater recognition on the basis that there are multiple grounds of discrimination.

"It's not just about a woman being raped in terms of violence against women, which is bad enough, but it's also got to do with sexual orientation so it's another ground or level of unfair discrimination leveled against lesbians."

It was not the first time Gaca had been raped. She says she ran away from her home village, in the rural Eastern Cape, after the first rape when she was 15 years old and too afraid to press charges.

She says running was easier than dealing with a community that didn't accept lesbians.

She moved to Khayelitsha Township, a sprawling shanty town near Cape Town, Africa's "gay capital" where she hoped to find tolerance.

Instead, she was confronted by more hate. "Being a lesbian in Khayelitsha is like you are being treated like an animal, like some kind of an alien or something," she said.

While there are no official statistics on corrective rape, there have been enough publicly reported incidents to spark widespread alarm.

This time Gaca is fighting back.

New York-based Human Rights Watch recently conducted interviews in six of South Africa's nine provinces and concluded: "Social attitudes towards homosexual, bisexual, and transgender people in South Africa have possibly hardened over the last two decades. The abuse they face on an everyday basis may be verbal, physical, or sexual -- and may even result in murder."

The group added: "This is a far cry from the promise of equality and non-discrimination on the basis of 'sexual orientation' contained in the country's constitution."

Most known victims, like Gaca, are poor and black and so are the perpetrators, prompting many to ask how a people who fought against discrimination during apartheid can today treat some of its most vulnerable in such a violent manner.

Siphokazi Mthathi, South African director at Human Rights Watch, said: "We've failed to make it understood that there is a price for rape. Sexism is still deeply embedded here. There is still a strong sense among men that they have power over women, women's bodies and there's also a strong sense that there's not going to be consequences because most often there are no consequences."

Interpol estimates that half of South African women will be raped in their lifetime. But corrective rape is not even recognized as a hate crime and rights groups say few victims report their cases to the police.

But Gaca did.

In many African countries being gay is illegal. In South Africa, those entrusted with enforcing the country's "tolerant laws" now stand accused of re-traumatizing victims.

"When a woman is raped she is re-raped by the system and for me this is a big thing because it's a serious violation of our constitution and the duties that are placed on the state in terms of what the state needs to do for survivors," Sanger said.

CNN saw the treatment meted out to survivors firsthand with Gaca as she trekked from police station to police station trying to first find, and then get answers from, her investigating officer.

He was the third assigned to her case since she reported the attack in December 2009 and she eventually found him at the sexual offences unit in Bellville, a 30-minute drive from her home.

Despite the sensitive nature of her case, he met her in the wide, open office.

When Gaca asked why the police had failed to interview her alleged attacker's friend, who witnessed the rape, another officer in the room told her: "I never take a statement from a suspect's friend."

He added: "The suspect's friend is obviously going to say you are in a relationship with the suspect or that he didn't see anything. The only statements that are important here are the ones from your friend, a neutral person or a neighbor. Not someone who was there watching while you were being damaged and he wasn't helping."

CNN requested an interview with the investigator and was referred to his superiors, before being granted an interview with South Africa's Minister of Police, Nathi Mthethwa, who promised an investigation.

"I feel bad," the minister said. "I feel bad about all these things. That is why I'm saying people who are responsible have a case to answer."

No action has so far been taken against the police officers who not only treated Gaca with disdain but who she also had to push every step of the way to do their job.

When they let her alleged attacker go without taking DNA evidence, potentially crucial in proving his guilt, it was Gaca who insisted they re-arrest him.

After neglecting to question the eyewitness who was allegedly there throughout the incident, it was Gaca who forced the police to talk with him.

She says she sat in a car while they questioned him, as he leaned in through an open window to tell the police officer what he saw of the assault, forcing Gaca to once again relive the experience.

South Africa's Victims' Charter was drafted in 2004, granting seven fundamental rights to every victim of crime. Among them is the right to be treated with fairness and with respect to your dignity and privacy.

Gaca says these rights are ideals she has never experienced. Yet she's determined to press on.

She said: "They always get away with it. I'm just pushing so that there will be a different story on my case. Maybe if this guy could be sentenced or something happens to him I think a lot of my friends will report their cases because some of the lesbians, they don't report their cases, they don't go to the police station because they know that it will just be a waste of time."

Nearly two years after reporting her case, Gaca is still awaiting her day in court, still hoping for justice, and still fighting.

Zukiswa Gaca was 15 when she ran

away from her home in rural South Africa after being raped. In

Khayelitsha, near Africa's 'gay capital' she was again targeted again, a

victim of what's called 'corrective rape.'

Zukiswa Gaca was 15 when she ran

away from her home in rural South Africa after being raped. In

Khayelitsha, near Africa's 'gay capital' she was again targeted again, a

victim of what's called 'corrective rape.'

No comments:

Post a Comment