CNN

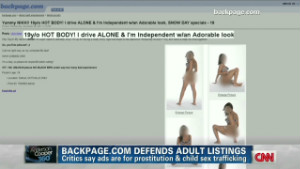

Girls wearing almost nothing at all, suggesting all sorts of sexual acts, listed on page after page of Backpage.com's escorts section. When she looked closer at the photos, she noticed something eerie.

She could recognize the rooms.

Ritter is a meeting planner at Nix Conference and Meeting Management of St. Louis. She and her co-workers work with 500 hotels around the world and visit about 50 properties annually. She can identify many hotel chains used in escort ads by their comforters, bathroom sinks, air conditioning units and door locks. Sometimes, she can also identify a specific property.

Meet Kimberly Ritter, sex trafficking sleuth.

A child protection code of conduct

Meeting planner Kimberly Ritter

Ritter has become a force in the international anti-trafficking movement, where she uses her expertise to identify the mainstream middle-end and high-end hotels used by traffickers.

She negotiates with hotels to fight trafficking at their properties, while also trying to convince hotel general managers that it's good business to fight trafficking through signing the Tourism Child-Protection Code of Conduct, a voluntary set of principles that businesses can adopt to fight trafficking. Her firm has created a version of the code for meeting planners and was the first signatory a few weeks ago.

Ritter hopes to recruit other planners to sign on to the code.

Once Ritter and her co-workers realized they could have an impact, "we thought this should be something all meeting planners could do," she said.

Although anti-trafficking organizations can't be sure how many people are forced into commercial sex work, the United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking estimates that human trafficking is a $32 billion business worldwide, with $15.5 billion coming from industrialized countries. (That includes forced sexual and nonsexual commercial labor of adults and children.)

An estimated 100,000 to 300,000 children are at risk of commercial sex exploitation in the United States, according to End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT), which created the tourism code. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline (888-373-7888) has recorded 46,000 phone calls over the past four years requesting information, reporting tips about trafficking and connecting about 3,600 victims of sex trafficking to social services. (The hotline takes calls about sex or labor trafficking.)

Trafficking isn't simply sex for sale

Sex trafficking isn't prostitution, which is engaging in sex with someone for payment. The crime of sex trafficking has three parties: one person holding the victim, while using "force, fraud or coercion" to make the victim engage in sex acts for payment, and the third party paying for the sex, said Brad Myles, executive director of thePolaris Project, which operates the hotline with funding from the U.S. government. If the victim is a child, no force, fraud or coercion is required for the sex to be a crime.

Escort ads posted online don't obviously state that sex with children is being sold, Ritter said, but customers who want children know to look for words like "fresh," "candy" and "new to the game." The underage victims are often runaways and victims of sexual abuse who are vulnerable to pimps promising modeling jobs, money, food and drugs.

After a pimp and customer make a deal, usually online or over the phone, hotels are an obvious place where the sex can take place. "There's privacy, a neutral place for a customer to come to, certain amount of anonymity and you don't have to stay long term," said Noelle Collins, an assistant U.S. attorney and human trafficking coordinator for the Eastern District of Missouri, who prosecutes these cases. "This can happen anywhere, but hotels are logical places where it could be found."

Sex trafficking wasn't on Ritter's mind when she met with the U.S. Federation of the Sisters of St. Joseph to book the federation's 2011 conference. That year, the nuns decided to take a stand on the issue. "We've always done some type of social action [at our conference]," said Sister Patty Johnson, executive director of the federation, which encompasses the 16 congregations of Sisters of St. Joseph in the United States. "We like to leave the city [we visit] a tiny bit better than when we came."

The nuns told Nix they wanted their hotel to sign the tourism code of conduct developed byECPAT, a worldwide network of organizations and individuals that fights commercial sex exploitation of children. Hilton Worldwide, Wyndham Worldwide, Carlson Rezidor Hotel Group (which includes the Radisson brand) and Delta Air Lines are all signatories to the code. After Ritter's initial online research turned up hotels she recognized, she agreed to raise the issue with their potential venues.

Hotels can train to fight trafficking

Many hotel executives have security measures designed to fight trafficking but express concern about being publicly identified with the issue. An exception is Millennium Hotel St. Louis general manager Dominic Smart. After learning about the problem, Smart got his parent company's permission to become a pilot program. Often, hotel executives don't want customers to think their hotels have a prostitution or sex trafficking problem. (The code requires annual reporting.) Smart, who said he hasn't had a case yet, didn't worry about it.

"We felt it was our responsibility to get involved and fight human trafficking," said Smart, whose hotel signed onto ECPAT, went through training for managers and line staff, and hosted the nuns' conference.

Training of hotel staff is key, said Michelle Gulebart, project coordinator for ECPAT-USA. Hotel managers may never spot the signs of sex trafficking, but housekeeping and room service employees often know something isn't right. They're just not sure what. "Hotel rooms are used as venues for exploitation," Gulebart said. "A pimp might hold up one or two girls in a room and might run traffic out of a room. They'll post ads on a website and send a girl to the room next door."

Red flags to watch for: Someone besides the guest rents a room, checks in without luggage and leaves the hotel. The child left in the room may seem confused about his or her own name; may appear helpless, ashamed, nervous or disoriented; may show signs of abuse such as bruising in various stages of healing; or may have tattoos that reflect money or ownership.

The child usually doesn't have any spending money or identification; cannot make eye contact; and wears clothes printed with slogans such as "Daddy's Girl" or inappropriate clothes for the weather. Sometimes, the child will come on to various men during the check-in process.

"We've trained them on the red flags, what to look for," Smart said. "If they see them, they report it to their manager and we would take over from there. The manager can assess and go to the police if need be."

Guests can report signs of trafficking

Hotel guests can also keep their eyes open for those red flags, said social worker Theresa Flores, an Ohio-based survivor of underage sex trafficking and an anti-trafficking activist. Guests who see the red flags can simply call the national hotline to report their suspicions, without ever leaving their names. Flores often travels to cities with big sports events and political conventions to educate hotel and motel owners, donating thousands of bars of soap listing the hotline for victims and witnesses to trafficking.

Most of the country's state attorneys generaland many anti-trafficking activists blame Backpage.com and other websites for not doing enough to fight sex trafficking. Backpage's lawyer says the company takes many steps to fight the problem.

"Any adult ads that are posted are monitored in real time, 24/7," wrote Steve Suskin, legal counsel for Village Voice Media, which owns Backpage, in an e-mailed statement to CNN.com. "All nudity is banned, even for adult ads, and anyone who attempts to post an ad that's suggestive of an underage or exploited minor is immediately reported to NCMEC [the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children], which is designated by the FBI to alert local law enforcement to rescue any child at risk in a hotel or other location."

Unlike other websites, Backpage doesn't allow Web posters to post anonymously, Suskin wrote.

"Backpage charges $1.00 to post in personals, because it holds users accountable and provides credit card information to police so they can identify, locate, arrest and prosecute those who use common carriers to prey on children," he wrote. "We continue to invest millions of dollars in human, technological, and other resources to detect and report suspected child predators and to help law enforcement apprehend and prosecute them."

With so much of the sex trafficking business migrating to the Internet, the crime still has to take place somewhere. "Hotels can really be part of the solution," said Myles, the Polaris Project executive director. "These are crimes, these are ways that women are being mistreated, and these are forms of violence against women. A lot of hotels don't want to be associated with it."

http://edition.cnn.com/2012/02/29/travel/hotel-sex-trafficking/

No comments:

Post a Comment